Representation

The Ocean Hill-Brownsville Community Control Movement

Since at least the 1930s Black and Puerto Rican parents in New York City had been demanding that the school system hire more teachers and principals that reflected the backgrounds of their children. Many White educators had low expectations of Black and Puerto Rican children and excessively disciplined and suspended them instead of working to bridge gaps in understanding and respect. In order to become a teacher you had to pass a series of written and oral exams, and migrants from the South and Puerto Rico felt that the exams were biased against them. Even if they passed, hiring was often first-come-first served or arranged through personal networks, both practices that disadvantaged non-White candidates that were new to the profession and not well-connected.

By the mid-60s, White educators and parents had consistently refused to integrate the city's schools. A group of Black teachers organized the African-American Teachers Association, and parents demanded to have a say in who taught their children, as well as the school budget and curricula. If the city would not integrate, then they wanted “community control” of their segregated schools. In 1967 the Board of Education authorized parent-elected Governing Boards to run the schools in three experimental districts in Harlem, the Lower East Side, and Ocean Hill-Brownsville.

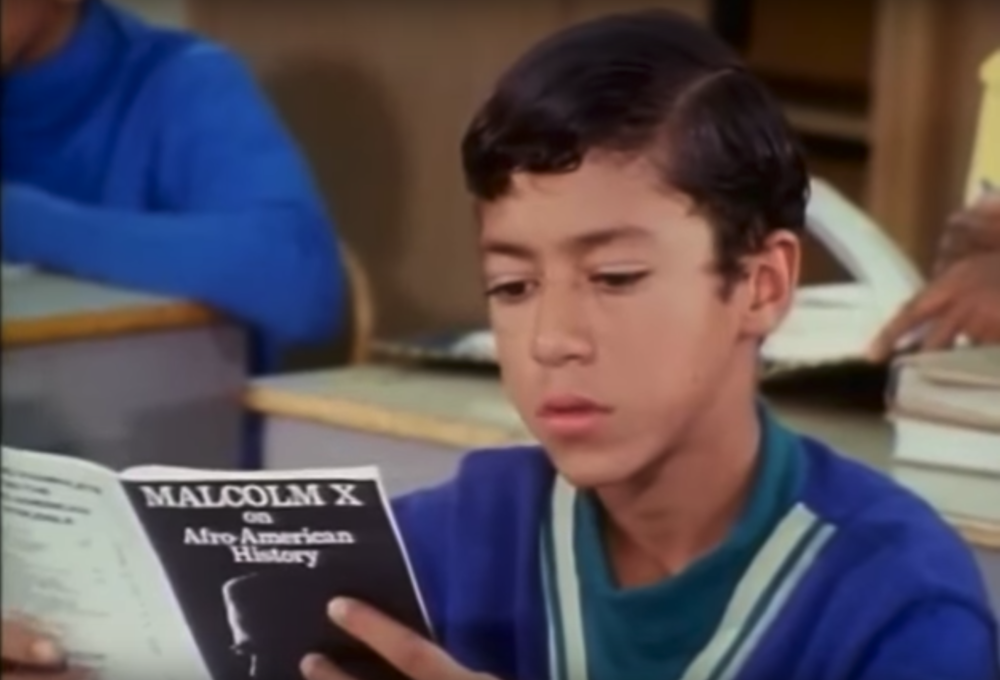

The Ocean Hill-Brownsville board hired a Black superintendent and the city’s first Latino and Asian-American principals. Members of the African-American Teachers Association taught students about the histories, cultures and languages of Africa. The students responded: “You felt more accepted. You weren't the outsider in your own school. They were a part of your environment. I mean, they were black, you can identify with them and they can identify with you. Just as simple as that, there's no big mystery.”

In the spring of 1968, the Ocean Hill-Brownsville board attempted to transfer a group of predominantly White Jewish teachers and supervisors out of the district. The unions saw this as a threat to their job security and accused the board of anti-Semitism; the conflict culminated in three strikes in the fall of 1968, which shut down the schools citywide for months. The board hired new teachers to replace the strikers. Most of the new teachers were also White and Jewish, but they were willing to work under the leadership of parents and educators of color to prove that all children could perform at a high level if they were treated with dignity and affirmed in their culture.

Ultimately, the Board of Ed. and teachers’ union negotiated an end to the strikes and an end to the community control experiment. Community control only lasted for three years, but for many students the experience of having Black, Latino and Asian-American educators as role models lasted a lifetime.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Eyes on the Prize, Part 9 (last segment): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ktcv6BOL38

Inside Ocean Hill-Brownsville: A Teacher’s Education 1968-69, by Charles S. Isaacs:

https://www.amazon.com/Inside-Ocean-Hill-Brownsville-Education-Excelsior/dp/1438452969