Reform to Revolution

_

During the early 60s, the collective consciousness was centered around obtaining civil rights through changing existing institutions. However, the limits and failures of these reforms, ongoing police brutality, economic exploitation and international struggles caused activists in the U.S to look for a new method of change that was directed at the roots of these problems. Around the late 60s, a collective consciousness emerged centered around revolution.

But what was this new Revolutionary Consciousness and what made it different from the mainstream civil rights struggle? What solutions and methods did activists create? And how did this change schooling within the struggle for liberation?

Why was there an evolution from reform to revolution in the late 60s?

As the conversation continued and also began to address events that were unfolding at the time, division began to rise among SNCC organizers as many critiqued the limits of legislative equality, the failure of reform, and nonviolent strategies; a desire for a new radical method of change brewed.

Reflect: How do you create change without relying on the government?

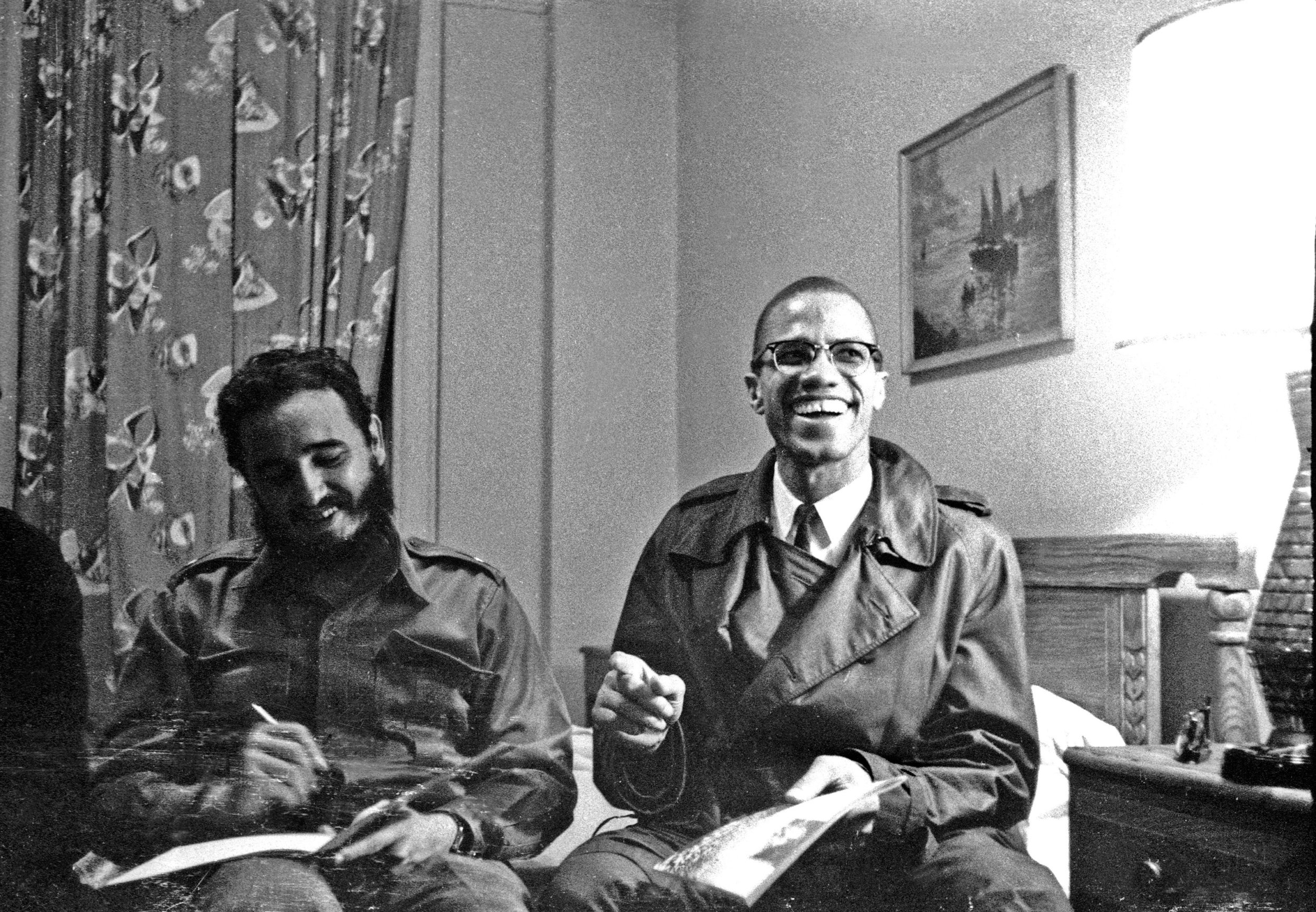

The New Consciousness: Internationalism

Black American activists saw African Independence Movements as intimately connected to their struggles here in the U.S. They also expressed solidarity with broader struggles for liberation against imperialism in places like Cuba, China, Venezuela, Guatemala, Bolivia, Palestine and elsewhere.

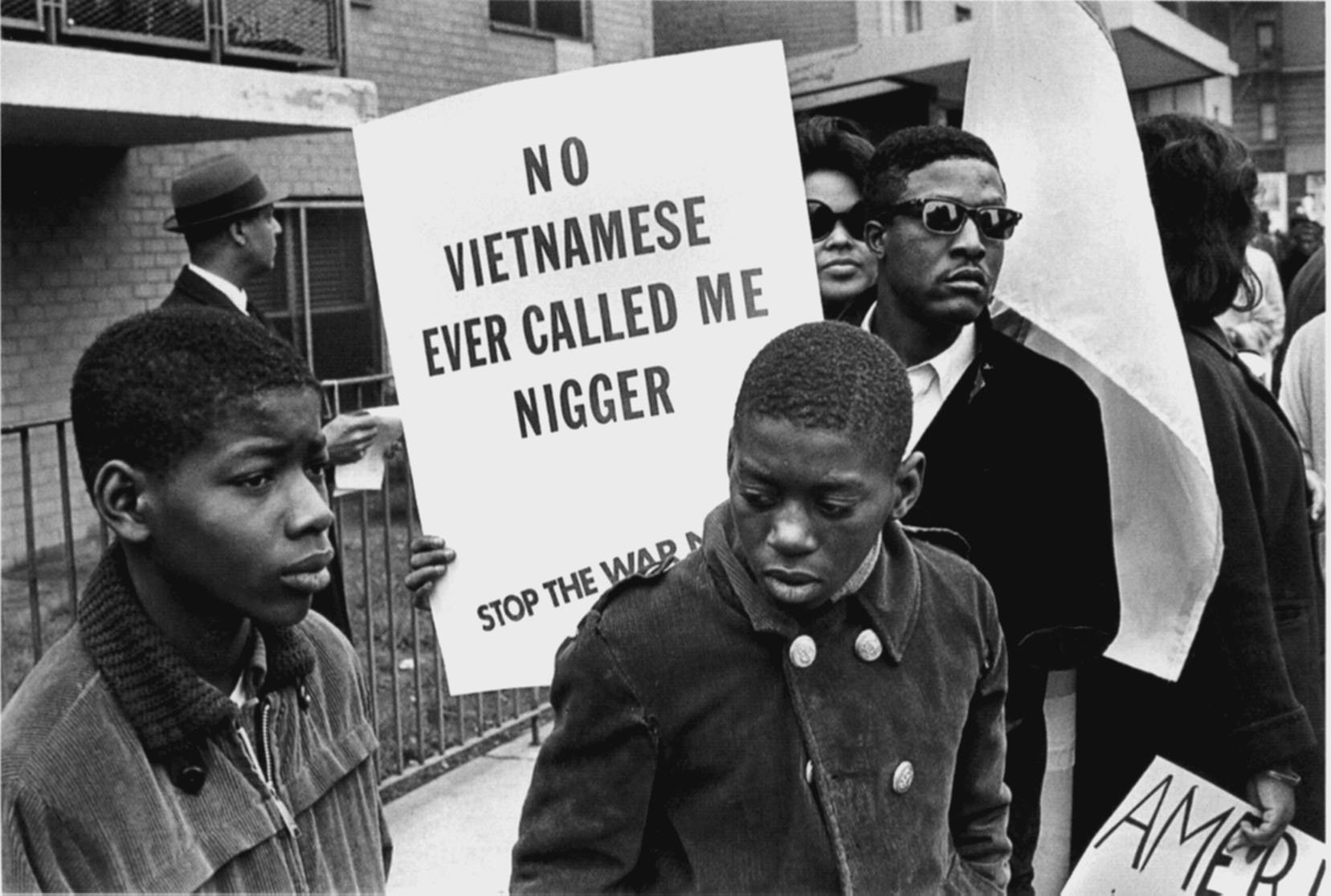

The Vietnam War was another factor since it revealed naked U.S imperialism and how the U.S put more money into protecting its economic interests abroad as opposed to addressing unemployment and poverty in the U.S.

Reflection: How and why do you think Black American activists saw their struggles as connected to those around the world?

Reflection: Do you see similarities today?

“An organization which claims to be working for the needs of a community - as SNCC does - must work to provide that community with a position of strength from which to make its voice heard. This is the significance of black power beyond the slogan.”

— Stokely Carmichael, “What we want” (1966)

The New Consciousness: Armed Self-Defense & Anti-Capitalism

In spite of civil rights legislation, unemployment, housing conditions, and poverty got worse for Black and Brown communities, showing activists that the problem was capitalism and the exploitation it allowed.

In response to ongoing police brutality, urban uprisings (sometimes called “riots”) became increasingly militant. Low-income Black and Brown communities demanded the right to self defense against the extreme violence they experienced from the police.

Who determines what violence is acceptable and why?

The limited impact of reforms on the living and working conditions of Black, Brown, and Indigenous Americans led many to demand power to the people. They no longer looked towards legislative reform to bring about the demands they wanted. Instead, they demanded self-determination, the ability to create and control their own institutions in the community.

Women, queer, and trans people of color were prominent leaders and thinkers within these movements. They confronted the sexist attitudes of male activists who did not (yet) see movements for gender & sexual liberation as central to their struggle.

Activists advanced their new consciousness through radical experiments in schooling, healthcare, housing, community safety, and other needs both inside and outside of the system.

Reflect: What does “people power” look like? What does it feel like?

The reform consciousness that animated the civil rights movement of the early 60s was primarily focused on addressing racism within the United States and demanding equal civil rights as democratic citizens.

The revolutionary consciousness that was arising in the late-60s added a more central critique of the relationships between racism and capitalism, and it looks at this as an international struggle for human rights and self-determination, meaning the right to be treated like your life matters, and to control your own life and future.

This is not a rigid distinction, it’s not like there was some meeting at which folks decided to stop talking about reform and start talking about revolution. But this summarizes how many activists’ language and analysis were evolving in this moment.

These were not new ideas at all. Black Communists like Claudia Jones and Paul Robeson had long expressed these sorts of internationalist anti-capitalist critiques, but they had been largely suppressed by the U.S. government.

Revolutionary Schools for Liberation

Building on the earlier model of Freedom Schools, activists advanced their new consciousness through radical experiments in schooling for liberation both inside and outside of the system.

Los Angeles SNCC’s Liberation School

Director Angela Davis (1967-68)

Part-time movement school: a school started by activists to further the goals of their movement.

Los Angeles, California

Curriculum: local and international liberation movements, community organizing, and political consciousness raising towards revolutionary action.

Black Panther Party’s Oakland Community School

Director Ericka Huggins (1970-1982)

Full-time independent school

Oakland, California

Curriculum: Black and African history, international solidarity with oppressed people, daily field trips within the community to critically examine the inhumane conditions the Black community lived in and their capitalist roots, youth justice committee to address school discipline.

Ocean Hill-Brownsville Demonstration District

Superintendent Rhody McCoy (1967-1970)

Public school district

Brooklyn, New York

Curriculum: Afro-Latin American Studies, the city’s first bilingual Spanish program, self-paced and ungraded literacy and math, readings about international struggles against racism and capitalism.

“Our children receive the nutrients that are needed to develop physically and mentally, so they can survive this corrupt system and build a new one that serves the people.”

— Emory Davis, Minister of Culture, Black Panther Party

Limits and Legacies

All three of these experiments in schooling came to an end due to combinations of government repression, internal conflict, and financial difficulties.

Their innovations are ancestors to today’s demands for culturally responsive education, restorative justice, and community schools.

But are they still rooted in an INTERNATIONAL consciousness critical of CAPITALISM and claiming POWER TO THE PEOPLE?

-

Carmichael, Stokely, and Charles V. Hamilton. 1967. Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America. New York: Vintage Books.

King, Martin Luther. 1967. Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? Boston: Beacon Press.

Davis, Angela Yvonne. 1974. Angela Davis: An Autobiography. New York, NY: Random House.

Forman, James. 1997. The Making of Black Revolutionaries. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. Lubin, Alex. 2014. Geographies of Liberation. Chapel Hill, N.C: UNC Press Books.

Blain, Keisha N. 2018. Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Newton, Huey P., 1974. “Intercommunalism.” Viewpoint Magazine: https://viewpointmag.com/2018/06/11/intercommunalism-1974/

Gore, Dayo F. 2011. Radicalism at the Crossroads: African American Women Activists in the Cold War. NYU Press.

Tyson, Timothy B. 2009. Radio Free Dixie: Robert F. Williams and the Roots of Black Power. Univ of North Carolina Press.

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (a.k.a. Kerner Commission). 1968. New York: Bantam Books. Digitized: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015000225410&view=1up&seq=1&skin=2021

“The Road Not Taken” https://belonging.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/haas_institute_road_not_taken_kerner_publish_may_2019.pdf

Angela Davis, Women of the Black Panthers: A Discussion in the Wake of Huey Newton’s Death: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kQ99Pm3Jql4

Muntaqim, Jalil A. 2010. We Are Our Own Liberators: Selected Prison Writings

Oakland Community Learning Center, 1977: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9dYsjDqUdr

Eyes on the Prize, Episode 9 Power! (1966-1968)

Isaacs, Charles S. 2014. Inside Ocean Hill-Brownsville: A Teacher’s Education, 1968–69. Albany, NY: Excelsior Editions.

Lewis, Heather. 2013. New York City Public Schools from Brownsville to Bloomberg: Community Control and Its Legacy. New York, N.Y: Teachers College Press.

Rickford, Russell John. 2016. We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.